Lately, I've been interviewing candidates for a Senior Angular Developer role, and I've ended up rejecting the majority of them. Am I a jerk for that? Maybe. But here's what I've realized from these interviews: we live in a bubble.

Most of us spend our day-to-day work calling APIs, caching data, and displaying it to users. We do this for years, and it leads us to believe we've mastered frontend development, especially a framework like Angular.

With this article, I want to walk through some of the technical questions I like to ask during interviews, all while exploring a deeper thought: "Am I really a senior developer, or do I just think I am?"

Before diving into the questions and sample answers, there's a broader discussion worth mentioning: Who's more valuable - a generalist or a specialist?

Someone who's worked across many domains (CI/CD, backend, databases, frontend, etc.), or someone who's deeply specialized in a single technology and only has surface level knowledge of the rest? That's a question only the interviewer can answer, based on the needs of the team. In my case, I was always looking for a specialist, hence following list of Angular focused interview questions. Finally, this is my personal list, feel free to critique or customize it for your own hiring process.

- General Questions:

- What does it mean to be a senior developer ?

- Do you prefer declarative or imperative programming?

- Would you use a state management library or a custom implementation?

- Angular Questions - General:

- How would you achieve a parent - child component communication ?

- What is the role of

NgZonein Angular, and when would you opt out of Angular's change detection? - What is and when to use an Injection Token ?

- What are resolution modifiers and how to use them ?

- Why would you use a

trackfunction in a for-loop and how it works ? - What is the the difference between

providersandviewProviders? Can you provide an example when to use either of them ? - Why

pipesare considered safe in a template, but regular function calls (not signals) are not ?

- Angular Questions - Signals:

- How would you convince your team to migrate a project from Observables to signals ?

- Can you explain the diamond problem in Observables and why it doesn't occur with signals?

- When to use

effectanduntrackedin a signal based application ? - Are life-cycle hooks still needed in a fully signal based application ?

- Angular Questions - RxJS:

- What is a higher-order observable and how they differ ?

- What is the difference between

share()andshareReplay()? - What does this code do ? -

scan()+expand()

General Questions

These are my go to questions at the very start of the interview process. There are no right or wrong answers here, what I'm really interested in is the developer's personality and thinking style. After all, this is someone who will be working closely with me and the rest of the team, and ideally, we want people who share a similar mindset or programming philosophy.

What does it mean to be a senior developer ?

This question helps me understand how I should approach the person I'm interviewing. As I mentioned earlier, there's often a pendulum swing between being a generalist and a specialist, so I like to hear how the candidate defines a senior developer. Most answers I get sound something like:

"Understanding the framework (Angular) very well and mentoring junior developers."

That's a pretty standard response, and I usually follow it up with:

"Alright, so if a senior should know the framework really well, is it okay for me to ask hard questions and expect you will be able to provide answers for them?"

What I'm really trying to grasp is how the candidate sees themselves, whether they feel they've reached a senior level and whether they've dealt with complex, challenging problems. This way, we set some expectations for the interview process, not defined by me, but by the candidate themselves.

Personally, I have a slightly broader view of what makes someone a senior developer. Yes, you should understand the framework well, but I'd also expect you to:

- Initiate and lead technical improvements, like addressing tech debt, and be able to pitch those ideas to higher ups.

- Push back (respectfully) on product or feature decisions that don't make sense or may harm long-term goals of the product.

- Know how to give and receive feedback during code reviews.

- Recognize when to Google something, when to ask a peer, and when it's worth gathering a few people for a brainstorming session.

- Care about the product and collaborate closely with product owners.

Do you prefer declarative or imperative programming?

You might say this is a theoretical question, and it is, but I like to ask it because it reveals how candidates think about code structure and maintainability. Most candidates respond with, “I don't know the difference”.

If you Google this question, you'll see something like: “Declarative programming focuses on what needs to be done, while imperative programming focuses on how to do it”.

In Angular terms, here's one way to think about it. Imperative programming involves mutating variables in multiple places, often with manual logic to track side effects. Declarative programming, by contrast, involves defining a value or behavior in one place, often through computed, signal, or RxJS streams. I highly recommend checking out Joshua Morony's video on this topic. Here is a coding example:

// Imperative Programming

@Component({ template: ` ... ` })

export class ChildComponent {

private readonly wsService = inject(WsService);

private readonly apiService = inject(ApiService);

displayedData = signal<string[]>([]);

constructor(){

// load existing data

this.apiService.existingData$.subscribe((data: string[]) => {

this.displayedData.set(data);

});

// listen on WS new data push

this.wsService.newData$.subscribe((data: string) => {

this.displayedData.update((current) => [...current, data]);

});

}

}

// Declarative Programming

@Component({ template: ` ... ` })

export class ChildComponent {

private readonly wsService = inject(WsService);

private readonly apiService = inject(ApiService);

displayedData = toSignal(

merge(this.apiService.existingData$, this.wsService.newData$).pipe(

scan((acc: string[], curr: string) => [...acc, curr], [] as string[])

),

{ initialValue: [] });

}

The imperative version manually subscribes to two streams (existingData$ and newData$) and mutates the displayedData signal in separate steps. Each data source is handled independently, which can lead to duplicated logic and harder maintenance as complexity grows.

In contrast, the declarative version merges both streams and uses scan to build up the displayedData in a single, unified expression. It avoids manual subscriptions and keeps logic in one place. This makes the code more predictable, easier to test, and less errors. Overall, the declarative approach describes what should happen, while the imperative one controls how it happens.

Would you use a state management library or a custom implementation?

The question is designed to brainstorm with the candidate. Some developers lean toward libraries like NgRx, Akita, or NGXS, while others prefer simpler, custom built state solutions using services, RxJS or signals. Both approaches are valid. What I'm really curious about is whether the candidate can justify their choice, present some trade-offs, and mention potential drawbacks of the alternative.

A senior developer should articulate decisions clearly, even when their opinion differs from their peers or contradicts the tech stack we are currently using. The provided answer will not change how I look at the candidate, I just want to see how can they argue toward one solution they see fit.

Angular Questions - General

How would you achieve a parent - child component communication ?

A simple question with a catch. Most candidates mention @Input()/@Output() bindings, or using a shared service with a Subject or a signal for communication.

// Input/Output example

@Component({ selector: 'app-child', template: ` ... ` })

export class ChildComponent<T> {

cSelected = output<T>();

cData = input<T[]>();

}

@Component({

imports: [ChildComponent],

template: `<app-child

[cData]="pData()"

(cSelected)="pSelected.set($event)" />`

})

export class ParentComponent {

pData = signal<string[]>(['a', 'b', 'c']);

pSelected = signal<string>('');

}

// Shared Service example

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class SharedService<T> {

store = signal<T | undefined>(undefined);

}

@Component({ selector: 'app-child', template: ` ... ` })

export class ChildComponent {

service = inject(SharedService<string[]>);

onPushData(){

this.service.store.set(['a', 'b', 'c']);

}

}

@Component({ imports: [ChildComponent], template: `<app-child />` })

export class ParentComponent {

storedData = inject(SharedService<string[]>).store

}

These are valid answers, but not enough for a senior level developer. I expect to also hear about:

- Custom two-way binding

- Model inputs

- Control Value Accessor

Custom two-way binding is achieved when the child component has an input and an output with the same property name, but the output uses the Change suffix. This syntax enables the “banana-in-a-box” [(data)] binding in the template. When the child emits a value via cDataChange.emit('something'), it directly updates the parent's pData signal or property.

@Component({ selector: 'app-child', template: ` ... ` })

export class ChildComponent {

cData = input<string>('');

cDataChange = output<string>();

onDataChange(){

this.cDataChange.emit('something');

}

}

@Component({

imports: [ChildComponent],

template: `<app-child [(cData)]="pData" />`

})

export class ParentComponent {

pData = signal('Hello World');

}

Model inputs offer syntactic sugar over manual two-way binding. Instead of defining two separate properties (@Input and @Output) and emitting values manually, you can use model() to bind once and let Angular handle the rest. The model() binding works both with signals and non signal properties passed from the parent.

A common use case is within custom form controls. This is not yet a signal form example, but so far the closest we can get. Inside a child component, we display an input (custom input, maybe with some specific functionality), and whenever the user types something, the ngModel emits the data into cData , and since it's a model(), it will once again emit the data to the parent pData.

@Component({

selector: 'app-child',

imports: [FormsModule],

template: `<input [(ngModel)]="cData" /> `

})

export class ChildComponent {

cData = model<string>('');

}

@Component({

imports: [ChildComponent],

template: `<app-child [(cData)]="pData" />`,

})

export class ParentComponent {

pData = signal('Hello World');

}

Control Value Accessor (CVA) is ideal when the child component acts as a custom form control. Implementing ControlValueAccessor allows the component to integrate with Angular's forms APIs, either reactive or template-driven.

I mostly use control value accessor when creating reusable component in a UI library or when the child is something like a custom search-select component. Imagine searching for goods in an amazon like webapp, that when you type a good's prefix, it makes an API call, and then you have a dropdown of possible options.

@Component({

selector: 'app-custom-input',

imports: [FormsModule],

template: `<input [ngModel]="value" (ngModelChange)="onInput($event)"/>`,

providers: [{

provide: NG_VALUE_ACCESSOR,

useExisting: forwardRef(() => CustomInputComponent),

multi: true

}]

})

export class CustomInputComponent implements ControlValueAccessor {

value = '';

// callbacks for the ControlValueAccessor

private onChange = (value: string) => {};

private onTouched = () => {};

// called when input changes

onInput(value: string): void {

this.value = value;

this.onChange(this.value); // propagate change

this.onTouched(); // mark as touched

}

// required from ControlValueAccessor

writeValue(value: string): void {

this.value = value;

}

// required from ControlValueAccessor

registerOnChange(fn: (value: string) => void): void {

this.onChange = fn;

}

// required from ControlValueAccessor

registerOnTouched(fn: () => void): void {

this.onTouched = fn;

}

}

@Component({

selector: 'app-parent',

imports: [ReactiveFormsModule, CustomInputComponent],

template: `

<app-custom-input [formControl]="pDataControl" />

<p>Parent value: {{ pDataControl.value }}</p>

`

})

export class ParentComponent {

pDataControl = new FormControl('Hello World');

}

Control Value Accessor looks more complicated and takes time to implement, especially when creating a complex custom part of the form, since it allows integrations with reactive or template driven forms.

Worth mentioning, that some candidates also bring up using viewChild() to reference the child component from parent, or using local storage or cookies to pass data, which are valid answers, but I would avoid these solutions in production.

What is the role of NgZone in Angular, and when would you opt out of Angular's change detection?

The answer on this question can really demonstrate the candidate skills and the level of projects he has work on. You rarely run code outside of Angular's change detection, you consider it when you run into performance issues.

NgZone is a wrapper around JavaScript's event loop that allows Angular to know when to trigger change detection. Angular patches async operations like setTimeout, Promise, XHR, etc. using zone.js, so when those operations complete, Angular automatically runs change detection to update the view. This occasionally leads into performance issues if you're running lots of non UI related or high frequency code (scroll, setInterval). In those cases, you can opt out of Angular's change detection using NgZone.runOutsideAngular(), and manually re-enter with NgZone.run() only if needed.

For a practical example, I include my blogpost - Simple User Event Tracker In Angular, where I setup some global listeners on button clicks, input or select changes. They do not impact UI bindings, and the code runs in the background, therefore we can run it outside Angular's change detection system. Other options where to reach it for this options include integrating with analytics, tracking, or 3rd-party scripts that are passive.

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class ListenerService {

private trackerService = inject(TrackerService);

private document = inject(DOCUMENT);

private ngZone = inject(NgZone);

constructor() {

this.ngZone.runOutsideAngular(() => {

this.document.addEventListener('change', (event) => {

const target = event.target as HTMLElement;

if (target.tagName === 'INPUT') {

this.trackerService.createLog({

type: 'INPUT',

value: (target as HTMLInputElement).value,

});

}

// others ....

}, true);

});

}

}

What is and when to use an Injection Token ?

An InjectionToken is like a unique identifier or a name tag that Angular uses to locate and provide a specific value or service during dependency injection. You typically use new InjectionToken() when you want to provide a value that isn't a class such as a configuration object, primitive value, or interface-based dependency.

One common use case is running initialization logic at the app startup using the APP_INITIALIZER injection token token. While APP_INITIALIZER is now deprecated, the recommended replacement is the provideAppInitializer function.

bootstrapApplication(App, {

providers: [

provideAppInitializer(() => {

// init languages

// get data from cookies

// setup sentry

// etc ...

}),

],

});

You can also define custom injection tokens, commonly used when developing Angular libraries that require configuration from the consuming app. For instance, if your library makes API call and needs to know whether it should call a production or development API, the consumer can provide this value through a token.

// code in the library

export const API_ENDPOINT = new InjectionToken<string>('API_ENDPOINT');

// --------------

// in a different application/library

bootstrapApplication(AppComponent, {

providers: [

{

provide: API_ENDPOINT ,

useValue: '/prod/api'

},

]

}

What are resolution modifiers and how to use them ?

A great explanation on this topic can be found in Decoded Frontend - Resolution Modifiers (2021). While the video is slightly dated, but the concepts remain the same. When injecting a service, Angular allows you to configure up to four resolution modifiers via the second argument to the inject() function. Below is a brief overview of each, focusing on what I typically expect from a senior candidate.

private service = inject(SomeService, {

host: true,

optional: true,

self: true,

skipSelf: true

});

Optional() is used when the provided service / injection token may or may not be provided by the developer. Example is the APP_INITIALIZER Injection token. When Angular injects this token, it uses inject(APP_INITIALIZER, {optional: true}) , since you, as a developer can, but don't have to provide some executable code when angular initiates.

Self() forces Angular to resolve the dependency only from the current injector. It won't check parent injectors. This is especially useful in directives that should only operate on the element they're attached to. An example is adding an asterisk to required input fields. You use self when injecting NgControl, so it only pulls from the target element:

@Directive({

selector: 'input[formControlName], input[formControl]'

})

export class RequiredMarkerDirective {

private ngControl = inject(NgControl, {

optional: true,

self: true

})

constructor() {

if (this.ngControl?.control?.hasValidator(Validators.required)) {

// Add red asterisk

}

}

}

Angular itself uses self() internally, for example in ReactiveFormsModule or FormsModule to resolve sync and async validators used on the form.

SkipSelf() is the opposite of self. It tells Angular to skip the current injector and look in the parent. This is useful when a directive or component needs to interact with a container element, like a parent form. In the example below, when using the FormControlName directive on reactive forms, it tries to resolve the parent form name for the control.

@Directive({

selector: '[formControlName]',

providers: [controlNameBinding],

standalone: false,

})

export class FormControlName extends NgControl implements OnChanges, OnDestroy {

constructor(

@Optional() @Host() @SkipSelf() parent: ControlContainer,

// ... other injectors

)

}

Host() modifier limits resolution to the host component or directive. It prevents Angular from searching up the hierarchy. For instance, if a directive inside FinalComponent tries to inject FormGroupDirective using @Host(), Angular will only look inside FinalComponent, not any parent components that may contain the actual form.

@Directive({

selector: '[appHostFormDirective]',

})

export class HostFormDirective {

private formGroup = inject(FormGroupDirective, { host: true })

constructor() {

console.log('FormGroupDirective found:', formGroup);

}

}

@Component({

selector: 'app-final',

template: `

<form [formGroup]="form">

<input [formControlName]="'name'" appHostFormDirective />

</form>

`,

imports: [ReactiveFormsModule, HostFormDirective],

})

export class FinalComponent {

form = new FormGroup({

name: new FormControl<string | null>(null),

});

}

I rarely use these modifiers in day-to-day application development. They tend to become more relevant when building libraries or advanced directives. However, Angular itself uses them extensively, and reviewing its source code is a great way to see them applied effectively.

Why would you use a track function in a for-loop and how it works ?

The track function is a useful performance optimization that was often overlooked with the old *ngFor="let item of items" syntax. Fortunately, the new control flow @for() now requires you to specify a track function, which encourages better practices.

So, why is it important? Imagine you have a component that makes an API call to fetch a list of items, list of users, and displays them in the template. You also have a “reload” button to refetch this data (in case something has changed on the backend). Below is an example using the older *ngFor syntax to illustrate the issue:

@Component({

selector: 'app-child',

imports: [NgForOf],

template: `

<button (click)="onRerun()">re run</button>

<div *ngFor="let item of items()">

{{item.name}}

</div>

`

})

export class ChildComponent {

items = signal<{ id: string; name: string }[]>([]);

onRerun() {

// "fake api call" to reload data

this.items.set([{id: '100', name: 'Item 1'}, /* ... */ ]);

}

}

In this setup, every time onRerun() is triggered and the array is updated (even with the same content), Angular will re-render all elements in the DOM. That's because it can't tell which items stayed the same and why didn't. It result to performance loss and UI flickering, especially in long or complex lists. To prevent this, you use a trackBy function:

@Component({

selector: 'app-child',

imports: [CommonModule],

template: `

<ng-container *ngFor="let item of items(); trackBy: identify">

<!-- previous code -->

</ng-container>

`

})

export class ChildComponent {

// ... previous code

identify(index: number, item: { id: string }): string | number {

return item.id;

}

}

This tells Angular how to uniquely identify items in the array, commonly via an id. With a trackBy function (or track key in @for()), Angular can associate each item with its corresponding DOM element. When the data is reloaded, Angular compares these keys (not full object references), allowing unchanged items to be preserved in the DOM.

Why does this matter? Because DOM operations are expensive. Without proper tracking, Angular discards and recreates DOM elements for every item, even if the data hasn't changed. With tracking, the DOM elements stay in place, and Angular only updates bindings when necessary.

On the GIF below, the top list uses trackBy: identify while the second one does not. You can see the difference. The top list preserves DOM elements during data reload, whereas the second recreates them entirely each time.

With the new @for() syntax, Angular enforces the use of a track key for the same purpose. However, two common mistakes still happen:

- Using the object itself as the key - example:

@for (item of items(); track item). This does not work as expected because the reference to each item changes on every reload, even if the data is identical and it will re-render the UI every time, basically ignoring thetrackfunction. - Using

$indexas the key - example:@for (item of items(); track $index). This causes problems when an item is removed. Suppose you delete the 5th item in a list of 10, then every item after index 4 now has a new index, forcing Angular to re-render them all unnecessarily. In stateful components like forms, this leads to loss of input focus or cursor position, however using the$indexis okay for static lists.

Here's a comparison: the top row uses track item.id, and the second uses track $index. Watch how the first preserves DOM elements during removal. Here is a stackblitz example to play with.

What is the the difference between providers and viewProviders ? Can you provide an example when to use either of them ?

A great write-up on this topic is by Paweł Kubiak in his article Hidden Parts of Angular: View Providers. Below is a summary of his explanation, followed by a practical example.

“When you use providers, the service is available to the component itself, its template, any child components, and even to content projected into it using

<ng-content>.On the other hand,

viewProviderslimit the service's visibility strictly to the component's view. That means it's accessible only to the component and the elements declared directly in its template—but not to projected content or external child components.”

In most applications I've worked on, using providers or viewProviders were rare use-cases. Where I've seen this being showcased the most are examples with NGRX and generating dynamic components with configurable dependencies.

Let's take an example from a flight booking portal. On the final payment step you present two payment options - Stripe (default) and PayPal payments, allowing users to choose. Each option has a different implementation, but both rely on a common PaymentService abstraction:

export abstract class PaymentService {

abstract pay(): void;

}

@Injectable()

export class StripeService implements PaymentService {

pay() { console.log('Paid with Stripe!'); }

}

@Injectable()

export class PaypalService implements PaymentService {

pay() { console.log('Paid with PayPal!'); }

}

@Component({

selector: 'app-payment-button',

template: `<button (click)="handlePayment()">Pay</button>`,

})

export class PaymentButtonComponent {

private paymentService = inject(PaymentService);

handlePayment() {

this.paymentService.pay();

}

}

Of course in real life you would need to establish a connection with the payment provider, handle errors, etc. The PaymentButtonComponent button is using the abstract PaymentService, which means, we need to provide an instance of either the Paypal or Stripe service. To dynamically decide which implementation to use based on user selection, you can manually create and inject the appropriate provider. This example demonstrates destroying and re-instantiating the component with a different PaymentService provider each time:

@Component({

imports: [FormsModule],

template: `

<label>

<input type="checkbox" [(ngModel)]="usePaypal" /> Use PayPal

</label>

<ng-template #container />

`

})

export class TestComponent {

readonly usePaypal = signal(false);

readonly container = viewChild('container', {

read: ViewContainerRef

});

constructor() {

// init payment button

effect(() => {

const container = this.container();

const usePaypal = this.usePaypal();

untracked(() => {

if (container) {

this.loadComponent(container, usePaypal);

}

});

});

}

loadComponent(vcr: ViewContainerRef, usePaypal: boolean) {

// remove previous

vcr.clear();

const injector = Injector.create({

providers: [

{

provide: PaymentService,

useClass: usePaypal ? PaypalService : StripeService

}

]

});

// attach component to DOM

vcr.createComponent(PaymentButtonComponent, { injector });

}

}

This example shows how providers can be dynamically configured depending on runtime logic. We don't use providedIn: 'root' here, even if our services were globally provided, because using Injector.create() always results in new instances, overriding any singleton behavior.

Even if the candidate doesn't know the exact difference, that's still okay, but I would expect at least one example where they encountered a situation that a global service wasn't enough, they needed to use a provider to create multiple instances for whatever reason.

Why pipes are considered safe in a template, but regular function calls (not signals) are not ?

Pure pipes are only reevaluated when their input values change, which makes them efficient and safe to use in templates. On the other hand, function calls in templates are executed on every change detection cycle.

So while {{ name | uppercase }} in the template is safe, {{ someHeavyFunction() }} will be called many times per second, which is rarely what you want. As Angular docs say: “by default all pipes are considered pure, which means that it only executes when a primitive input value is changed.”

Here I do a shameless plug including my article where I dove deeper into how the Implementation of Angular Pipes works. Under the hood, pipes create a caching object, and for a specific input, they perform the pipe's logic and store the result in the cache. Then, when change detection runs again with the same input, the pipe first checks the cache. If the output was already computed, it simply returns the cached value, making it an O(1) operation.

Angular Questions - Signals

Signals in Angular were first introduced in May 2023 with version 16, and there was quite a bit of buzz even before their official release. What fascinates me is when a candidate says, “Yeah, signals are here, but we worked on an older project and never migrated, so I never had a chance to try them out.” That's a red flag… what else can I say? As a senior developer, you're expected to have an understanding of newer features and how they work, even if you haven't used them in production yet.

How would you convince your team to migrate a project from Observables to signals ?

This question tells me two things. First, whether the person has a solid understanding of signals, and second, whether they've ever initiated a larger tech debt refactor on a project. I believe a senior developer should actively drive technical improvements and come forward with such initiatives. One solid answer might be something like:

“Angular, and overall the whole frontend ecosystem, is clearly moving toward signals. There's even a TC39 proposal to support signals natively in JavaScript. Most of the new Angular APIs, like the Resource API, are designed to work with signals. Signals also simplify state management, since you can both listen to changes and synchronously read their current value.”

Can you explain the diamond problem in Observables and why it doesn't occur with signals?

So far, this question has had a very high failure rate, but I like to see how candidates react to a topic they've likely never encountered in an Angular interview.

I first came across the diamond problem in the article from Mike Pearson - I changed my mind. Angular needs a reactive primitive. He argues why RxJS, even if loved, may not be the safest choice for Angular's long term and why SolidJS chose signals.

Mike talks about the diamond problem and the following example is heavily inspired from his blogpost. We are specifically curious about the behavior of the combineLatest operator.

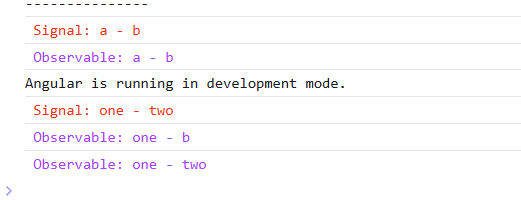

Let's say we have an effect that listens to two signals. Signals are synchronous and batched, meaning that if both signals are updated one after another, the effect will still run only once. However, if we use combineLatest, it emits every time a dependency changes, resulting in multiple emissions even for the same update cycle.

export class TestComponent {

prop1 = signal('a');

prop2 = signal('b');

constructor() {

effect(() => {

const prop1 = this.prop1();

const prop2 = this.prop2();

console.log(`Signal: ${prop1} - ${prop2}`);

});

combineLatest([

toObservable(this.prop1),

toObservable(this.prop2)]

).subscribe(([p1, p2]) => console.log(`Observable: ${[p1} - ${p2}`));

setTimeout(() => {

this.prop1.set('one');

this.prop2.set('two');

}, 1000);

}

In the console output, you'll see:

- The

effectlogs only once, after both values are updated. - The

combineLatestlogs twice, once for each individual update.

This is a concrete example of the diamond problem - duplicated or excessive emissions due to shared dependencies in a reactive graph. Signals avoid this problem thanks to their synchronous and batched behavior.

I know this may be more of a “gotcha” question, so you could rephrase the question into: “Why can Observables like combineLatest lead to unnecessary emissions, and how do signals prevent that?”

When to use effect and untracked in a signal based application ?

Angular docs has a section use cases for effects, that talks about when effects should be used. Based on that I expect a response from the candidate something like:

"Use effect when you have no other alternative. For example when you need to rely on a reactive value and the other end isn't reactive. Use cases may include DOM API synchronizations, sending data into analytics, communication with a non-reactive library"

It's also important that the candidate has an understanding why the untracked function is needed when we want to remove dependency tracking in an effect. Problems I personally encountered many times were that an effect was reading multiple signals, but also modifying some, therefore it created an infinite cycle and was running all the time. Personally, I use untracked most of the time, leaving only the dependency signals outside of it. In the following example I want to focus on the input element when the button is clicked. I use afterRenderEffect which works similarly as effect, with the key difference being that it runs after the application has completed rendering.

@Component({

selector: 'app-focus-example',

imports: [FormsModule],

changeDetection: ChangeDetectionStrategy.OnPush,

template: `

<button (click)="editMode.set(!editMode())">

{{ editMode() ? 'Exit' : 'Enter' }} Edit Mode

</button>

<input #editInput [(ngModel)]="value" [disabled]="!editMode()" />

`

})

export class FocusExampleComponent {

editMode = signal(false);

value = signal('Initial value');

editInput = viewChild('editInput', { read: ElementRef });

constructor() {

afterRenderEffect(() => {

const editMode = this.editMode();

untracked(() => {

if (editMode ) {

// read the element reference once, without tracking it

const inputRef = this.editInput();

// defer the focus() until after the DOM is updated

setTimeout(() => {

inputRef?.nativeElement?.focus();

})

}

})

});

}

}

Are life-cycle hooks still needed in a fully signal based application ?

This question is great for brainstorming with a candidate, whether he understands these hooks and also how signals work. Based on my experience, many life-cycle hooks can be replaced by signals and reactive primitives:

NgOnInit(NO) - Mostly replaceable withconstructororeffect(). This hook is traditionally used for initialization logic that depends on resolved inputs, data fetching, or setting up observers. For simpler logic,constructor()suffices, while more complex reactive scenarios are better handled witheffect().NgOnChange(NO) - Can be replaced withcomputed()oreffect(), as these can react to changes ininput()signal dependencies.NgAfterViewInit(NO) - Replaceable witheffect()to perform updates on DOM elements, usingviewChild()signal references as dependencies.NgAfterContentInit(NO) - Similar toNgAfterViewInit,effect()can handle initialization logic based oncontentChild()signal references or you can use the afterNextRender callback.NgAfterContentChecked/NgAfterViewchecked(NO) - are called after every change detection cycle, which makes them performance sensitive. You can replace them with afterRenderEffect which runs after the view has been rendered and a signal dependency changed.NgOnDestroy(NO) - For cleanup tasks such as unsubscribing from third-party libraries, clearing intervals, or other manual teardown logic that signals don't automatically handle you can inject DestroyRef and listen ononDestroyfor this purpose.

Angular Questions - RxJS

Even in a fully signal based application, there are still use cases where RxJS is a better alternative. From my experience, nearly everything can be implemented by signals, but RxJS sometimes offers a more declarative or composable approach, especially when dealing with complex async workflows therefore I open a debate about some RxJS topics.

What is a higher-order observable and how they differ ?

For an indepth reading about this topic I include a blogpost that I've made in the past Angular Interview: What is a Higher-Order Observable?. A good example is the classic search box use case, where on each keystroke, an API request is made. The candidate should be able to explain how the behavior changes depending on which higher-order observable operator is used.

export class TestComponent {

private readonly http = inject(HttpClient);

readonly control = new FormControl<string>('');

search$ = this.control.valueChanges.pipe(

// switchMap, concatMap, mergeMap, exhaustMap

switchMap((val) => this.http.get('...', {

val: val

}))

)

}

switchMap- cancels any ongoing request when a new value is typed. Ideal for search boxes, only the latest input matters.mergeMap- triggers all requests in parallel. Every keystroke results in a request, regardless of timing. Good for logging, but not ideal for searches.concatMap- queues each request and processes them sequentially, preserving order. Better for form submission flows, not live search.exhaustMap- ignores new values while a request is in progress. Useful to prevent duplicate requests (e.g., during button mashing), but bad for fast-typing search boxes. If you don't use theabortSignalfor the resource API, it works asexhaustMap.

What is the difference between share() and shareReplay() ?

Too much of a theoretical question? Not at all. In a legacy project, which still mainly relies on Observables, you may have situations where you use one of them to multicast values to subscribers. There are, however, occasional bugs, for example, when you navigate back and forth between pages. The next time you come back, you no longer have the current value, or you just retriggered logic that should have been cached by the shareReplay() operator. Or, you just ignore both and use BehaviorSubject.

Both share() and shareReplay() are RxJS multicasting operators. They allow multiple subscribers to share the same source observable, preventing duplicated side effects (like HTTP requests).

- Use

share()when you only want future subscribers to receive emissions. It doesn't retain or replay past values. Essentially, it converts a cold observable into a hot one. - Use

shareReplay()when you want new subscribers to immediately receive the latest emitted value(s). It's useful for caching scenarios where re-executing the source (e.g., an HTTP request) is costly or undesirable.

You can configure shareReplay() using options like:

bufferSize– The number of previous values to remember and replay to new subscribers. Typically set to1for simple caching.refCount– Whentrue, the observable automatically unsubscribes from the source when there are no subscribers. Whenfalse, it stays connected indefinitely (useful for shared streams).

What does this code do ? - scan() + expand()

Both scan() and expand() are rarely used in everyday Angular development. However, their presence can indicate that a candidate has encountered more complex problems, problems that go beyond the usual use of map, filter, or take operators. I like to show a practical example like this:

private paginationOffset$ = new Subject<number>();

loadedMessages = toSignal(this.paginationOffset$.pipe(

startWith(0),

exhaustMap((offset) =>

this.api.getMessages(offset).pipe(

expand((_, i) =>

(i < 2 ? this.api.getMessages(offset + 20) : EMPTY)

),

map((data) => ({ data })),

catchError((err) => of({ data: [] })),

startWith({ data: [] }),

),

),

scan(

(acc, curr) => ({ data: [...acc.data, ...curr.data] }),

{ data: [] as MessageChat[] },

),

), {initialValue: [] });

nextScroll() {

this.paginationOffset$.next(this.loadedMessages().data.length);

}

The code above represents a recursive API based pagination pattern. Every time the user triggers nextScroll() (for example, by clicking a "Load More" button), the number of already loaded messages is emitted into the paginationOffset$ subject. Inside the loadedMessages signal:

exhaustMapignores new emissions until the current inner observable completes. The user is unable to load more data until the first batch completes.expandis used to recursively call the API multiple times. We assume each call returns 20 messages. Usingexpand, we can simulate loading three pages in one shot (initial call + two recursive calls).scanaccumulates all the loaded messages into one stream without losing previously fetched ones.catchErrorensures that any failed API call doesn't break the chain.startWithensures the stream emits an initial empty state, avoiding undefined references.

Summary

Other notable questions may be:

- Describe a time you had to refactor legacy code in Angular, how did you approach it?

- How do you handle code scalability and performance in large Angular apps?

- What is OnPush change detection and when would you use it?

- What's the difference between

combineLatest,withLatestFrom, andforkJoinand how would you decide which to use? - What is you approach to testing, what mocking library do you use?

- How would you migrate an existing app to standalone components and Signals gradually?

- What is hydration, how you enable it, why is it needed?

Overall, these are the types of questions I lean toward. However, the most important one we always ask at the end is:

“Can you tell us about some more complex feature you have worked on in the past 1–2 years? What was the problem, and how did you solve it?”

The candidate may be missing some Angular specific knowledge, but they may have faced challenging problems, possibly even ones we're currently facing. Prior experience solving real problems often outweighs deep framework trivia, which can be learned over time.

Ultimately, it depends on your company's needs. Do you need a strong Angular expert who can refactor and migrate legacy code while minimizing future tech debt? Or are you looking for someone to join a broader team, where they'll grow with support from others? Decide for yourself.

Feel free to share your thoughts, catch more of my articles on dev.to, connect with me on LinkedIn or check my Personal Website.